Seven historic stones in the Diamond Fund collection

Diamond Fund is a unique collection of gems, jewelry, and natural nuggets, stored and exhibited in Moscow Kremlin, Russia. The Kremlin's Diamond Depository dates back to the reign of Peter 1, who decreed for the most valuable treasures to become the property of the Russian state, not only of the Royal Family. From then on, precious regalia, insignia and secular jewelry belonging to several generations of Russian rulers would be stored in the Diamond Room in St. Petersburg until 1914. When WWI broke out, the collection was moved to Moscow and placed in the Armory basement, where it would stay for nearly 8 years. The Diamond Depository was established in 1922, but only in 1967, when the Soviet state was celebrating its 50th anniversary, were the treasures placed on public display.

After revolution 1917, the collection became known as The Diamond Fund of the RSFSR and, after the formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1924, as The Diamond Fund of the USSR. It was during this period under the supervision of A.E.Fersman that the above-mentioned four-volume album was produced, volume one of which was published by the People's Commissariat of Finance in 1925. For the first time in the study of Russian jewelry here was a work containing photographic reproductions of artistic and historical items. The album included invaluable material for specialists on the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the precious stones. This was also the first time that signed articles and articles with a hypothetical attribution had been made public. As A.E.Fersman remarked, they had created "a kind of catalog, compiled and vouchsafed by an authoritative commission, which serves as an official list of valuables that have survived in spite of all the difficulties of the revolutionary period and are the property of the Republic."At that time Academician Alexander Fersman selected seven rarities in the Diamond Fund collection, which he called "historic" stones, they were the pride of the Imperial collection because of their remarkable size, purity, color and transparency. Among the famous stones are Red Spinel, Orlov Diamond, Shah Diamond, Table Portrait Diamond, Ceylonese Sapphire, Columbian Emerald and Chrysolite that will be described in this article.

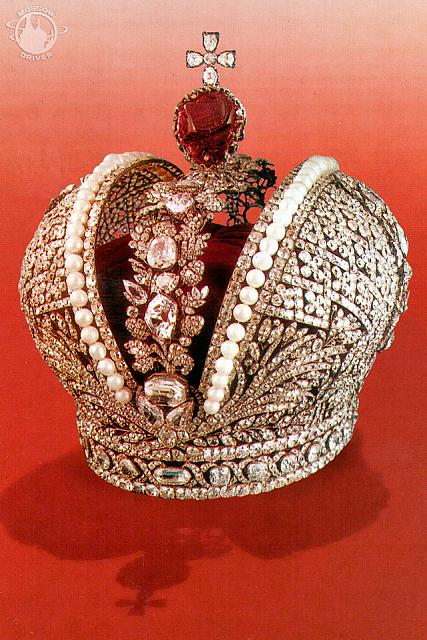

1. Red Spinel - 398.72 carats

Let us start from a miracle of nature, a gorgeous deep Red Spinel of natural form weighing 398.72 carats that was adorned the famous the Great Imperial Crown by court jeweler Jeremie Pauzie, who created the crown for the coronation of Catherine the Great in 1762. The stone is gleaming with all possible shades of deep red, on the crown it was framed with diamonds and topped by a small diamond cross. In spite of doubts expressed concerning the origin and use of red gemstones in the treasury, and the need for a more detailed study of each surviving specimen, which will undoubtedly take considerable time, we shall outline the history of this huge spinel as it is usually related.

Red stones of such great size, uniform color and ideal transparency and purity are a rare occurrence in nature, which explains why spinels, rubies and red sapphires have always been specially revered and very costly. In the East a good red stone of medium size could be exchanged for two racehorses.

The spinel which figures in our story was purchased in China in 1676 on orders from Peter the Great's father, Tsar Alexis Romanov. When the tsar's envoy to China, Nikolai Spafary, set off for Peking to establish diplomatic and trading relations, he was instructed, inter alia, to look for rare stones for the treasury. During this period, the seventeenth century, there was no large-scale mining of gemstones in Russia and most stones were imported from distant India. China did not, unfortunately, justify Russia's expectations concerning the purchase of rubies and emeralds. Spafary did find out, however, that a certain high-born courtier possessed a red "lal" of singular beauty. In those days the Russian word "lal" was used to denote a spinel. After lengthy negotiations the owner eventually agreed to show him the red beauty. The stone made a great impression on the envoy, but purchasing it proved to be no easy matter. The original asking price was unacceptably high and only as a result of long bargaining and negotiations did the stone end up in the hands of Spafary, who wrote in his report: "paid a very high price indeed..." The "very high" price was 2,672 rubles, incidentally. In negotiating the deal, the Chinese"... swore there was no other stone like it in the whole state and insisted that it should be kept secret, or they would be executed for selling such a precious object to be taken out of the country..." Many publications referring to the sale of this unique gem state that the stone was acquired from the Chinese Emperor K’ang-hsi. However, thanks to a study of archival documents made by R.V.Demicheva, senior research worker at the Kremlin Museums, it has been shown that a purchase of this kind could not have been made directly from the emperor. This would not have been in keeping with Chinese etiquette at that time, and the emperor is unlikely to have feared execution for such an act.

In Russia Spafary's rare acquisition was greatly appreciated. The stone was used as a fitting adornment for the crowns of the Russian monarchs. In 1762 it appears to have been removed from Empress Anna Ioannovna's crown and placed on the new crown being made for the coronation of Catherine the Great. The empty place on Anna Ioannovna's crown, it can be assumed, was taken by another red stone, the tourmaline that Alexander Menshikov presented to Catherine I.

Sparkling and flashing with iridescent fire the huge deep-red spinel on the top of the crown enhances the impression of sumptuous grandeur. The magnificent precious stones, the unexcelled skill of the makers, their refined taste and sense of proportion explain why specialists refer to the Great Imperial Crown as "sheer perfection" and "a symphony in stone unequalled in any other European state regalia."

As Catherine the Great had hoped, the crown was used at subsequent coronations of all the Russian emperors right up to the last, that of Nicholas II in 1896.

2. Orlov Diamond - 189.62 carats

The Orlov Diamond is the main ornament on the Imperial gold scepter. The scepter consists of three polished sections divided by paired bands of brilliants and is particularly valuable because of the famous stone mounted in it. This large, completely pure and transparent crystal with a barely noticeable bluish-green tinge weighs 189.62 carats and is another of the seven historic stones in the Diamond Fund collection. Today this splendid diamond is called the Orlov, but that was not always the case. Numerous specialists agree that the stone was found at the famous Golconda deposits in India in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. It was probably part of a larger crystal that split off along the plane of the cleavage. The weight of this larger crystal was thought to be about 400 carats.

The first person to be associated with the diamond was a member of the Grand Mogul dynasty, Shah Jehan, whose name means "ruler of the world". On the orders of Shah Jehan, who belonged to the tenth generation of Timurids and was renowned as a lover of precious stones, the diamond was cut in the form of a high Indian rose. Rose is the name given to a special cut in which the lower part of the stone remains untouched, while the upper part is shaped like a dome, by applying tiny, usually triangular facets to the surface. The old Indian masters traditionally tried to preserve as much of the stone's original size and natural form as possible, which is why they sometimes did little more than polish the existing natural facets. In this case, in spite of all the cutter's efforts, the diamond lost almost half its weight during cutting. Legend has it that Shah Jehan was so angry at this he not only refused to pay the master for his work, but even ordered his possessions to be confiscated by the treasury as compensation. At that stage the large piece of diamond was cut with 235 small triangular facets. The stone was still referred to as a diamond, however. A diamond is not called a brilliant until is has been cut at the bottom as well as the top.

The Orlov diamond still retains its original cut, which makes it even more valuable and important for specialists. In the middle of the seventeenth century Shah Jehan was deposed by his son, who cast his father, the once mighty ruler, into prison. In 1665 the new ruler, Aurangzeb, allowed the celebrated

French traveller and expert on precious stones Jean-Baptiste Tavernier into his treasury. Tavernier was astounded by what he saw there and asked permission to weigh and draw the largest and most valuable stones. This was graciously given, and today we are able to consult Tavernier's work where, among the various descriptions and drawings, we find a stone remarkably like the one that now bears the name of the Orlov diamond.

Tavernier drew a large rose diamond, extremely high on one side and almost flat on the other. In the lower rib of the stone he drew a small defect in the form of a tiny incision with an opaque spot. The weight of the stone as recorded by Tavernier (191.55 carats) is almost that of the Orlov diamond. In 1666 Aurangzeb's treasury acquired another large diamond cut in the form of an Indian rose. It weighed approximately 186 carats and apparently formed a magnificent pair with the crystal we know as the Orlov diamond. Legend has it that long ago these two large stones so similar in form and size served as the eyes for the statue of a god in a sacred temple in the town of Srirangam in the south of India. The stones were then stolen, it is thought by a French soldier.

The next owner of the stone was the celebrated Shah Nadir who ruled Persia from 1736. (The name Persia was officially changed to Iran in 1935) This ruler's fate was most interesting, so we shall say a few words about him, particularly as his name crops up later. After joining the service of Shah Tahmasp II, Nadir mounted some successful campaigns against the Turks and Afghans who had seized a number of provinces in Persia. The people saw Nadir as their liberator from foreign rule and gave him the utmost support. In 1732 Nadir deposed his patron and placed the latter's infant son Abbas on the throne, then had himself appointed regent. In 1736 Nadir declared himself shah, after which he continued to conquer neighboring countries, including Northern India, where he captured and looted the treasures of Delhi. The mighty empire created by him depended on a regime of cruelest tyranny, as a result of which in the 1740s there were increasingly frequent uprisings by conquered peoples and feudal internecine strife. Nadir Shah was killed as a result of a conspiracy by one of the military feudal groupings. After the ruler's death in 1747 the empire founded by him collapsed.

Leaving the dread ruler's sad fate let us now return to the story of the big diamonds that interest us, one in particular. After entering the treasury of Shah Nadir, the diamonds were used to adorn his throne. In the opinion of Academician Fersman one of them was called the Darya-I-Noor (sea of light) and the other was the Koh-I-Noor (mountain of light). Does this mean that the Orlov diamond was once called the Darya-I-Noor? Specialists now know that the Darya-I-Noor never left Persia, where it was taken from India by Shah Nadir.

We shall now attempt to reconstruct the subsequent history of the stone in which we are interested, the Orlov diamond. Many authors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries studied the famous diamonds and compared their fates. The history of our stone is interwoven with that of many other famous diamonds, not only the Darya-I-Noor, but also the Great Mogul and the Regent. But are there any grounds for trying to identify them with our stone? It would appear not. The Orlov diamond differs in both form and weight from the Darya-I-Noor, which remained in Iran, and from the Regent, which is now in the Louvre. In the case of the Great Mogul, however, there are more grounds for identification. Alexander Fersman, referring to Tavernier's study, compared the size, form, weight and quality of the two diamonds and even the small defect in the lower part of the stone. This comparison led him to assume that the Great Mogul, which had been lost, and the Orlov diamond in the Diamond Fund were one and the same stone. It is most tempting to believe such an eminent specialist as Academician Fersman, but for the time being we shall be cautious and leave the question open for further study. So what was the future fate of our diamond? It is now time to say a few words about that.

After the death of Shah Nadir, during the popular disturbances in Isfahan our diamond again fell into the hands of a thief. It then frequently changed owners, until it came into the possession of a rich Armenian merchant called Gregory Safras Hadjiminas, a native of New Julfa in Persia. In the seventeenth century the Julfa merchants enjoyed the right of transit trade through Russia on favorable terms granted to them after members of a merchant clan presented Tsar Alexei Romanov with a Diamond Throne studded with a mass of precious stones, including 800 diamonds. Today the throne is on display in the State Armory. The numerous gifts brought by traders through Russia included precious stones.

From the point when the diamond came into Saphras's possession, the fate of this huge stone can be traced from documental evidence. In 1982 Nauka publishers brought out a book by A.P. Baziyants entitled «Над архивом Лазаревых» (The Lazarev archive). This interesting study answers the question as to how the diamond found its way into the treasury of the Russian court.

After obtaining the diamond, Gregory Saphras make an attempt to sell it in Astrakhan. He did not manage to find a buyer in Russia, however. So he sold his right of ownership to half the stone to his nephew, a rich banker and court jeweler, known at the Russian court by the name of Ivan Lazarev. Having agreed that his nephew would look for a buyer in Russia, Saphras left for Amsterdam where he deposited the diamond in the bank. Hence the stone’s alternative names of the Amsterdam or Lazarev diamond. Another name one sometimes meets is the Russian diamond. Today, however, the stone is known by one name only, the Orlov diamond. How it acquired this name we shall now explain in detail.

So Saphras sold his right to half the stone to Ivan Lazarevich Lazarev and entrusted him with the task of finding a buyer. This decision would seem to be a most sensible one, as Ivan Lazarev was closely connected with court life in the capital, St Petersburg. He was from an aristocratic family which headed the Armenian colony in St Petersburg and Moscow and was famed for setting up the Institute of Oriental Languages. The Lazarev family, wealthy owners of factories, mines, and metallurgical works, have gone down in the history of Russo-Armenian relations of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Ivan Lazarev's political and financial activities brought him close to many courtiers, including such an influential one as Count Grigory Orlov. The Orlov brothers played an active part in the coup of 28 June 1762 which brought Catherine the Great to the throne. On the Empress’s name-day, 23 November 1773, the count gave Catherine a special present: instead of the traditional bouquet of flowers, Grigory Grigorievich presented his sovereign with a diamond of great size and beauty. He had purchased it from Ivan Lazarev for 400,000 roubles. On the basis of documents studied Baziyants argues convincingly that the true purchaser of the diamond was the Empress herself. It was agreed that the stone would be purchased in installments over seven years. Only the first installment was paid by Count Orlov, however. Payment for the rest came from Catherine's cabinet. Evidently the enlightened monarch could not allow such a vast sum as 400,000 roubles to be paid openly out of the state coffers, so she decided to effect payment through Count Orlov, whose name has thus been linked forever to the world-famous diamond. As proof of the above, we quote the title of the relevant document from the Matenadaran archive: "On the acquisition for the treasury through ... Lazarev of the said diamond from the courtier Shafrasov for 400,000 roubles."

Thus one of the world’s most beautiful and famous diamonds entered the Russian treasury to adorn the top of the Imperial sceptre.

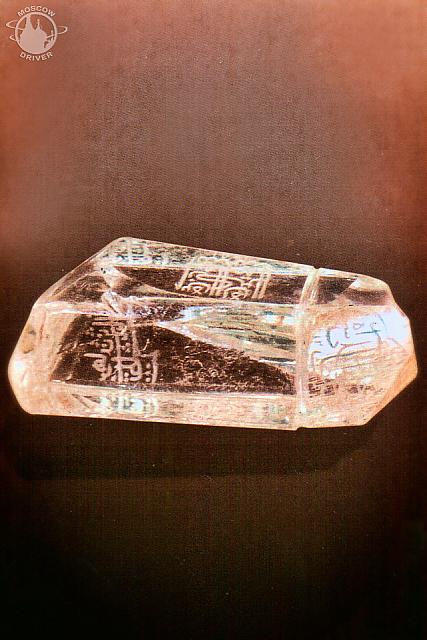

3. Shah Diamond - 88.70 carats

Of more interest to us here, however, are the gifts that were brought to Russia, and one in particular. This is the famous diamond known today all over the world as the Shah Diamond. Originally and for a considerable time it was called the "Prince's Stone" or "Solitaire of Hosrev-Mirza".

The Shah diamond may at first glance not seem as impressive in size and brilliance as the equally famous Orlov diamond. Yet it weighs no less than 88.70 carats, has retained its natural form and is famous to specialists all over the world. The diamond has a light yellowish-brown tint. This is because the surface of the stone is covered with tiny cracks invisible to the naked eye with brownish iron oxide mottling. Yet the stone is perfectly pure. Another interesting feature is that the diamond itself can relate its own history. Ancient masters engraved it with three inscriptions in Arabic containing the names of its owners with dates according to the Eastern calendar. In his study of the stone Academician Fersman wrote: "From the crystallographic point of view, the Shah is a large octahedral crystal with the rounded ribs customary for a diamond, elongated along one octahedral rib... Some of the facets ... have survived quite untouched, and some have been replaced by polished facets, but in such a way that generally all eight facets of the octahedron have survived in their natural form ... What is more, four facets of the octahedron or the new facets replacing them have been cut by a deep furrow, and three polished surfaces have finely engraved inscriptions in the Persian language..."

All three inscriptions are beautifully engraved, although each in a slightly different type of engraving. They were read and explained by the Russian orientalist Academician S.F.OIdenburg. The oldest in terms of technique is the cruder, but deep inscription that reads: "Burkhan-Nizam-Shah the second. Year 1000" This inscription was carved when the stone belonged to the ruler of the Indian province of Achmednager in 1591. Later, as a war trophy, it came into the possession of Akbar, a member of the Grand Mogul dynasty. After that the stone came to the attention of Akbar's grandson Shah Jehan (on whose orders the diamond now known as the Orlov was cut). It was under him that the next inscription appeared: "Jehan-Shah Son of Jehangir-Shah. 1051" Translated into the modern calendar the inscription was engraved in 1641. Legend has it that the stone hung on a silk cord over the throne of the rulers of India. The throne itself was made of gold adorned at the top with a peacock studded with a vast number of diamonds, emeralds, rubies, spinels and garnets. In 1739 the Persian Shah Nadir conquered and looted the capital of the Grand Moguls, carrying off all their treasure. Documents show that there were more than sixty crates of precious stones alone and it took eight camels to transport the gold throne. Once in the treasury of the shahs of Persia the stone lay there undisturbed for more than a century. During the celebrations of the thirtieth anniversary of Fath-Ali-Shah's reign the third and most beautiful framed inscription was engraved on the diamond. It reads: "The ruler Kadjar Fath AN Shah Sultan. 1242." This means that it was engraved on the orders of a shah from the Kadjar dynasty in 1824. Of great interest is the round groove up to 0.5 mm deep for hanging the crystal on a gold or silk cord as a talisman, mentioned by Academician Fersman. It was cut so perfectly that he called it "a brilliant piece of technology" and was amazed that it"... could have been done in India given the state of the cutting industry at the beginning of the seventeenth century." Here it should be noted that a diamond can only be worked by another diamond, i.e. there is no harder substance in nature. So the Shah diamond can tell the world its remarkable story, which makes it perhaps the most unusual stone in this respect.

4. Table Portrait Diamond (Tafelstein) - 25 carats

Another historic stone, the Table Portrait Diamond known as the "Tafelstein", is considered to be the largest specimen of table diamond in the world. This 25-carat stone is 4 x 2.9 cm and 2.5 mm deep. For comparison, two portrait diamonds from the Iran treasury weigh 15 and 20 carats. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century there was a fashion for brooches, bracelets, signet rings, and earrings decorated with watercolor miniatures that were covered with glass to protect them. The massive Portrait Diamond Bracelet of neo-gothic form, made in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, bears a miniature watercolour portrait of Emperor Alexander I. It is painted on ivory from a portrait by the English painter George Dawe. Dawe lived in St Petersburg for ten years. During this period he produced a whole series of works including some for the Portrait Gallery of heroes of the war of 1812 against Napoleon. The miniature portrait of Alexander I is covered not by glass, but by the world's largest table diamond, the shape of which is repeated by the watercolor. The diamond is a cleaved fragment of a larger stone. It is absolutely pure and transparent, except for a tiny air bubble in the corner by the mount. The stone would appear to have been found in India and cut there. Along the edges it is covered by a network of tiny facets in two tiers, but the surface is perfectly polished. When and how the diamond appeared in Russia and what was its earlier history remains a mystery to this day, although many attempts have been made to solve it. In 1893 a Professor Ball from Dublin, who was making a study of the world's most famous gemstones, addressed a request to the Minister of the Russian Court for material connected with the famous stones in the Russian collection. The official reply stated that no historical information about the table diamond existed.

5. Ceylonese Sapphire - 260.37 carats

The beautiful deep-blue Ceylonese Sapphire weighing 260.37 carats and set in a high mount of gold filigree decorated with diamonds is also one of the historic stones in the Diamond Fund collection.

In the nineteenth century, there was a fashion for large brooches, which were used to fasten big shawls also popular at the time. The logical center of this particular brooch is the splendid, perfectly pure and transparent sapphire with deep, even coloring. Only at the bottom is there a slight blur of minute mottling and small round depressions. The surface of the stone is covered with a complex pattern consisting of a multitude of hexagonal facets. The beauty of the sapphire is emphasized by the elegant frame of sparkling diamonds, which skilfully conceals the stone's thickness and highlights the shape by its wavy line. In terms of purity of tone, depth of coloring, quality of cutting and size (3.8 x 3.5 x 2.4 cm) this sapphire is one of the largest and most beautiful in the world. Academician Fersman wrote of it: "The famous Rospoli in Paris and the Duke of Devonshire's splendid sapphire pale by comparison with this one."

6. Columbian Emerald - 136.25 carats

Columbian Emerald weighing 136.25 carats and table cut to 3.6x3.25 cm. This remarkable gemstone, which in earlier times was called a smaragd and revered as the stone of life, spring and wisdom, is remarkable for its deep shade of green and pure, even coloring. As we know, a characteristic feature of emeralds is the presence of flaws. There is an old saying that an emerald without flaws is unattainable perfection. This is particularly true of large stones. The emerald in the exhibition has almost no flaws, and its six inclusions are so small as to be invisible to the naked eye. At a certain angle one can see scratches on the surface of the table, but they merely serve as evidence of the stone's great age, although there are no documents or legends about its past history. Academician Fersman attempted to give an approximate idea of its origin. In his reflections on this unique stone, he wrote: "It was probably found in the Middle Ages, the period of the discovery of America, and kept in one of the sacred temples of Columbia, then taken to India after the bloody struggle of the Portuguese. There it merged in with other gems in this country, until it reached the European market by the same mysterious ways in which the East so often sent valuables from its harems and treasuries to the counters of Western merchants." Fersman believed the stone's masterly cutting was the work of Indian masters. Emeralds have always been greatly valued by experts and gemstone lovers all over the world. There are many large specimens in national and private collections. Some exceed our stone in size and weight, but the Diamond Fund emerald is unique in its purity, beauty and deep rich green.

Columbian Emerald weighing 136.25 carats and table cut to 3.6x3.25 cm. This remarkable gemstone, which in earlier times was called a smaragd and revered as the stone of life, spring and wisdom, is remarkable for its deep shade of green and pure, even coloring. As we know, a characteristic feature of emeralds is the presence of flaws. There is an old saying that an emerald without flaws is unattainable perfection. This is particularly true of large stones. The emerald in the exhibition has almost no flaws, and its six inclusions are so small as to be invisible to the naked eye. At a certain angle one can see scratches on the surface of the table, but they merely serve as evidence of the stone's great age, although there are no documents or legends about its past history. Academician Fersman attempted to give an approximate idea of its origin. In his reflections on this unique stone, he wrote: "It was probably found in the Middle Ages, the period of the discovery of America, and kept in one of the sacred temples of Columbia, then taken to India after the bloody struggle of the Portuguese. There it merged in with other gems in this country, until it reached the European market by the same mysterious ways in which the East so often sent valuables from its harems and treasuries to the counters of Western merchants." Fersman believed the stone's masterly cutting was the work of Indian masters. Emeralds have always been greatly valued by experts and gemstone lovers all over the world. There are many large specimens in national and private collections. Some exceed our stone in size and weight, but the Diamond Fund emerald is unique in its purity, beauty and deep rich green.

The diamond mount in the form of a garland of stylized vine leaves alternating with big round brilliants was made in the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

7. Oval Chrysolite - 192.60 carats

And, finally, the seventh of the stones in the Diamond Fund that Academician Fersman classified as historic. This is the uniquely large and pure oval Chrysolite from the island of Zaberget in the Red Sea. This giant stone is 5.2 x 3.5 cm at its widest point and up to 1.1 cm high. As already mentioned, the name "chrysolite" comes from the Greek word meaning "gold stone". Because of its beautiful deep olive shade, the stone is also known incorrectly as the "evening emerald". It weighs 192.60 carats and is perfectly pure and transparent. The cut is a combination of large facets: the upper, slightly domed table is surrounded by tiered facets, while the lower section consists of numerous uneven rectangular facets. Chrysolites have been known and valued since antiquity. Together with lapis lazuli they were greatly valued by the Egyptian pharaohs, and in the Middle Ages became very popular with the Crusaders, who brought a large number of the "gold stones" to Europe. The Diamond Fund specimen was exhibited for many years without a mount, until 1984-1985 when jewelers in the Gokhran Experimental Jewelry-Making Laboratory produced one made with old-cut diamonds which emphasizes the beauty of this unique gem. In former times the chrysolite may have been a pendant, as modern restorers believe, but it could also have been used as a big fashionable brooch.Many years have passed since Academician Fersman highlighted these seven unique stones in the Diamond Fund collection, and today we can add to this list of rarities.

One such addition is a huge 250-carat Emerald. Although it is not of extremely high quality, the stone is noteworthy for its rare size and deep shade. The flaws in the stone consisting of a network of tiny factures do not spoil its appearance, but create the impression of a light frosty pattern on the green of the emerald. Academician Fersman assumed from the color that the stone came from the Urals, but its place of origin was established as Columbia by specialists in the 1980s.

Another Portrait Emerald in the collection is of interest not so much for its size or color, as its superb carving. Carved gemstones have always been highly valued by experts. Bracelets, brooches, diadems and rings were decorated with cameos in which the design was raised above the background, or intaglios, as in this case here, when the representation is lower in relation to the ground. The brooch in question is set with an exquisite 36-carat emerald bearing a carved profile portrait of Catherine the Great. The portrait was the work of Professor Johann Jager of the St Petersburg Academy of Arts in the second half of the eighteenth century. Emeralds are known to be unusually brittle so their cutting requires special skill. The stone's rich color is emphasized by two rows of close-set brilliants. The smooth gold mount of broad festoons was made later, in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The brooch was acquired by Gokhran from a private individual in the 1960s.

During the one-hour tour of Diamond Fund of Russia you can see all the seven historical stones and state regalia, a rare collection of gold and platinum nuggets, and also Russian-made jewelry. The largest diamonds found in this country include some remarkable specimens named after notable events or personalities, such as the Star of Yakutia, the Great Beginning, and the Yuri Gagarin diamonds.

About Me in Short

My name's Arthur Lookyanov, I'm a private tour guide, personal driver and photographer in Moscow, Russia. I work in my business and run my website Moscow-Driver.com from 2002. Read more about me and my services, check out testimonials of my former business and travel clients from all over the World, hit me up on Twitter or other social websites. I hope that you will like my photos as well.

See you in Moscow!